Comediants

Add a review FollowOverview

-

Founded Date August 24, 1955

-

Sectors كمبيوتر وشبكات

-

Posted Jobs 0

-

Viewed 34

Company Description

Artificial Intelligence Industry In China

The synthetic intelligence industry in individuals’s Republic of China is a rapidly developing multi-billion dollar market. The roots of China’s AI development began in the late 1970s following Deng Xiaoping’s financial reforms emphasizing science and innovation as the country’s primary productive force.

The preliminary phases of China’s AI advancement were sluggish and encountered substantial obstacles due to lack of resources and skill. At the beginning China was behind the majority of Western countries in regards to AI development. A majority of the research study was led by scientists who had received higher education abroad. [1]

Since 2006, the government of the People’s Republic of China has actually progressively developed a nationwide agenda for expert system development and became among the leading nations in synthetic intelligence research and advancement. [2] In 2016, the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) launched its thirteenth five-year plan in which it intended to become an international AI leader by 2030. [3]

The State Council has a list of “national AI teams” including fifteen China-based companies, consisting of Baidu, Tencent, Alibaba, SenseTime, and iFlytek. [citation required] Each company needs to lead the development of a designated specialized AI sector in China, such as facial recognition, software/hardware, and speech recognition. China’s fast AI development has actually considerably impacted Chinese society in many locations, consisting of the socio-economic, military, and political spheres. Agriculture, transportation, lodging and food services, and production are the top markets that would be the most impacted by more AI release.

The private sector, university laboratories, and the military are working collaboratively in numerous elements as there are couple of present existing boundaries. [4] In 2021, China published the Data Security Law of individuals’s Republic of China, its first nationwide law resolving AI-related ethical concerns. In October 2022, the United States federal government revealed a series of export controls and trade constraints intended to restrict China’s access to sophisticated computer system chips for AI applications. [5] [6]

Concerns have actually been raised about the impacts of the Chinese federal government’s censorship routine on the development of generative expert system and skill acquisition with state of the nation’s demographics. [7] [8]

History

The research and development of expert system in China started in the 1980s, with the announcement by Deng Xiaoping of the value of science and technology for China’s financial growth. [3]

Late 1970s to early 2010s

Artificial intelligence research and development did not begin up until the late 1970s after Deng Xiaoping’s financial reforms. [3] While there was a lack of AI-related research in between the 1950s and 1960s, some scholars think this is because of the influence of cybernetics from the Soviet Union despite the Sino-Soviet split throughout the late 1950s and early 1960s. [9] In the 1980s, a group of Chinese scientists launched AI research study led by Qian Xuesen and Wu Wenjun. [9] However, during the time, China’s society still had an usually conservative view towards AI. [9] Early AI development in China was difficult so China’s government approached these obstacles by sending out Chinese scholars overseas to study AI and further supplying government funds for research study tasks. The Chinese Association for Artificial Intelligence (CAAI) was established in September 1981 and was licensed by the Ministry of Civil Affairs. [10] The first chairman of the executive committee was Qin Yuanxun, who got a PhD in philosophy from Harvard University. [citation required] In 1987, China’s very first research publication on expert system was published by Tsinghua University. Beginning in 1993, clever automation and intelligence have become part of China’s national technology strategy. [9]

Since the 2000s, the Chinese government has actually even more broadened its research study and advancement funds for AI and the variety of government-sponsored research study tasks has actually considerably increased. [3] In 2006, China revealed a policy priority for the development of expert system, which was included in the National Medium and Long Term Prepare For the Development of Science and Technology (2006-2020), launched by the State Council. [2] In the same year, artificial intelligence was likewise mentioned in the eleventh five-year plan. [11]

In 2011, the Association for the Advancement of Expert System (AAAI) established a branch in Beijing, China. [12] At exact same year, the Wu Wenjun Expert System Science and Technology Award was founded in honor of Chinese mathematician Wu Wenjun, and it ended up being the greatest award for Chinese accomplishments in the field of expert system. The very first award event was hung on May 14, 2012. [13] In 2013, the International Joint Conferences on Expert System (IJCAI) was held in Beijing, marking the very first time the conference was kept in China. This occasion coincided with the Chinese federal government’s announcement of the “Chinese Intelligence Year,” a significant milestone in China’s advancement of expert system. [12]

Late 2010s to early 2020s

The State Council of China released “A Next Generation Artificial Intelligence Development Plan” (State Council Document [2017] No. 35) on 20 July 2017. In the document, the CCP Central Committee and the State Council advised governing bodies in China to promote the development of expert system. Specifically, the plan explained AI as a tactical innovation that has actually become a “focus of worldwide competitors”. [14]:2 The file prompted considerable financial investment in a number of strategic locations associated with AI and required close cooperation in between the state and private sectors. On the event of CCP basic secretary Xi Jinping’s speech at the very first plenary conference of the Central Military-Civil Fusion Development Committee (CMCFDC), scholars from the National Defense University wrote in the PLA Daily that the “transferability of social resources” between financial and military ends is an essential part to being a terrific power. [15] During the Two Sessions 2017,”expert system plus” was proposed to be raised to a strategic level. [16] The exact same year witnessed the development of multiple application-level uses in the medical field according to reports. [17] Furthermore, the Chinese Academy of Sciences (CAS) developed their AI processor chip research study laboratory in Nanjing, and introduced their first AI specialization chip, Cambrian. [citation required]

In 2018, Xinhua News Agency, in partnership with Tencent’s subsidiary Sogou, launched its very first synthetic intelligence-generated news anchor. [18] [19] [20]

In 2018, the State Council budgeted $2.1 billion for an AI industrial park in Mentougou district. [21] In order to accomplish this the State Council stated the need for enormous skill acquisition, theoretical and useful advancements, along with public and personal financial investments. [14] A few of the specified motivations that the State Council provided for pursuing its AI technique include the potential of artificial intelligence for industrial improvement, better social governance and maintaining social stability. [14] Since completion of 2020, Shanghai’s Pudong District had 600 AI business across foundational, technical, and application layers, with related markets valued at around 91 billion yuan. [22]

In 2019, the application of synthetic intelligence expanded to different fields such as quantum physics, location, and medical research. With the emergence of big language designs (LLMs), at the beginning of 2020, Chinese researchers began developing their own LLMs. One such example is the multimodal large model called ‘Zidongtaichu.’ [23]

The Beijing Academy of Expert system released China’s very first large scale pre-trained language design in 2022. [24] [25]:283

In November 2022, the Cyberspace Administration of China (CAC), Ministry of Industry and Information Technology, and the Ministry of Public Security collectively released the guidelines concerning deepfakes, which ended up being efficient in January 2023. [26]

In July 2023, Huawei launched its version 3.0 of its Pangu LLM. [27]

In July 2023, China launched its Interim Measures for the Administration of Generative Expert System Services. [28]:96 A draft proposal on basic generative AI services security requirements, including specs for data collection and model training was provided in October 2023. [28]:96

Also in October 2023, the Chinese government launched its Global AI Governance Initiative, which frames its AI policy as part of a Community of Common Destiny and aims to build AI policy discussion with establishing countries. [29] [28]:93 The Initiative has actually expressed concern over AI safety dangers, consisting of abuse of information or the use of AI by terrorists. [28]:93

In 2024, Spamouflage, an online disinformation and propaganda campaign of the Ministry of Public Security, started utilizing news anchors developed with generative expert system to deliver fake news clips. [18]

In March 2024, Premier Li Qiang released the AI+ Initiative, which plans to incorporate AI into China’s real economy. [28]:95

In May 2024, the Cyberspace Administration of China announced that it presented a big language model trained on Xi Jinping Thought. [30]

According to the 2024 report from the International Data Corporation (IDC), Baidu AI Cloud holds China’s biggest LLM market share with 19.9 percent and US$ 49 million in earnings over the last year. This was followed by SenseTime, with 16 percent market share, and by Zhipu AI, as the 3rd largest. The fourth and 5th biggest were Baichuan and the Hong-Kong listed AI business 4Paradigm respectively. [31] Baichuan, Zhipu AI, Moonshot AI and MiniMax were applauded by financiers as China’s new “AI Tigers”. [32] In April 2024, 117 generative AI models had actually been authorized by the Chinese federal government. [33]

As of 2024, numerous Chinese innovation companies such as Zhipu AI and Bytedance have actually introduced AI video-generation tools to competing OpenAI’s Sora. [34]

Chronology of major AI-related policies

Ministry of Science and Technology; Ministry of Industry and Infotech; the Central Leading Group for Cyberspace Affairs

National Development and Reform Commission; Ministry of Science and Technology Ministry of Industry and Infotech

Government goals

According to a February 2019 publication by the Center for a Brand-new American Security, CCP general secretary Xi Jinping – thinks that being at the forefront of AI technology will be vital to the future of international military and economic power competition. [35] By 2025, the State Council intends for China to make essential contributions to basic AI theory and to solidify its place as a worldwide leader in AI research. Further, the State Council goes for AI to become “the primary driving force for China’s industrial updating and economic transformation” by this time. [14] By 2030, the State Council intends to have China be the international leader in the advancement of artificial intelligence theory and technology. The State Council claims that China will have developed a “mature new-generation AI theory and innovation system.” [14]

According to academics Karen M. Sutter and Zachary Arnold, the Chinese federal government “looks for to meld state preparation and control while some functional versatility for companies. In this context, China’s AI firms are hybrid gamers. The state guides their activity, funds, and guards them from foreign competitors through domestic market defenses, developing uneven benefits as they expand offshore.” [36]

The CCP’s fourteenth five-year strategy declared AI as a top research study top priority and ranks AI first among “frontier industries” that the Chinese government intends to concentrate on through 2035. [3] The AI market is a strategic sector frequently supported by China’s federal government assistance funds. [37]:167

Research and development

Chinese public AI financing mainly focused on sophisticated and applied research study. [38] The government financing likewise supported numerous AI R&D in the private sector through endeavor capitals that are backed by the state. [38] Much analytic company research study showed that, while China is massively buying all aspects of AI advancement, facial acknowledgment, biotechnology, quantum computing, medical intelligence, and self-governing cars are AI sectors with the most attention and funding. [39]

According to national guidance on developing China’s modern industrial advancement zones by the Ministry of Science and Technology, there are fourteen cities and one county selected as a speculative development zone. [40] Zhejiang and Guangdong provinces have the most AI development in speculative areas. However, the focus of AI R&D differed depending on cities and local commercial advancement and ecosystem. For example, Suzhou, a city with a longstanding strong production market, greatly focuses on automation and AI infrastructure while Wuhan focuses more on AI executions and the education sector. [40] In connection with universities, tech companies, and nationwide ministries, Shenzhen and Hangzhou each co-founded generative AI labs. [25]:282

In 2016 and 2017, Chinese groups won the top reward at the Large Scale Visual Recognition Challenge, an international competition for computer system vision systems. [41] Many of these systems are now being incorporated into China’s domestic monitoring network. [42]

Interdisciplinary partnerships play an essential function in China’s AI R&D, including academic-corporate cooperation, public-private cooperations, and international cooperations and projects with corporate-government partnerships are the most typical. [1] China ranked in the top three worldwide following the United States and the European Union for the overall variety of peer-reviewed AI publications that are produced under a corporate-academic partnership in between 2015 and 2019. [43] Besides, according to an AI index report, China surpassed the U.S. in 2020 in the overall variety of global AI-related journal citations. [43] In terms of AI-related R&D, China-based peer-reviewed AI papers are mainly sponsored by the federal government. In May 2021, China’s Beijing Academy of Expert system launched the world’s biggest pre-trained language design (WuDao). [44]

Since 2023, 47% of the world’s top AI researchers had actually completed their undergraduate research studies in China. [28]:101

According to scholastic Angela Huyue Zhang, publishing in 2024, while the Chinese federal government has actually been proactive in controling AI services and imposing commitments on AI business, the total technique to its policy is loose and shows a pro-growth policy favorable to China’s AI industry. [28]:96 In July 2024, the federal government opened its very first algorithm registration center in Beijing. [45]

Population

China’s big population creates a massive amount of available information for companies and scientists, which uses a in the race of big data. Since 2024 [upgrade], China has the world’s biggest number of web users, producing huge quantities of information for maker learning and AI applications. [46]:18

Facial acknowledgment

Facial recognition is one of the most commonly used AI applications in China. Collecting these big quantities of information from its residents helps more train and expand AI capabilities. China’s market is not just conducive and important for corporations to more AI R&D but also uses significant financial possible attracting both worldwide and domestic firms to sign up with the AI market. The extreme advancement of the information and communication technology (ICT) industry and AI chipsets over the last few years are two examples of this. [47] China has actually become the world’s biggest exporter of facial recognition technology, according to a January 2023 Wired report. [48]

Censorship and material controls

In April 2023, [49] the Cyberspace Administration of China (CAC) provided draft steps stating that tech companies will be obliged to guarantee AI-generated content supports the ideology of the CCP including Core Socialist Values, avoids discrimination, appreciates copyright rights, and safeguards user data. [50] [25]:278 Under these draft measures, companies bear legal obligation for training data and content created through their platforms. [25]:278 In October 2023, the Chinese government mandated that generative artificial intelligence-produced material may not “prompt subversion of state power or the overthrowing of the socialist system.” [51] Before launching a big language model to the public, business need to look for approval from the CAC to license that the model refuses to answer certain questions associating with political ideology and criticism of the CCP. [8] [52] Questions related to politically delicate subjects such as the 1989 Tiananmen Square demonstrations and massacre or comparisons between Xi Jinping and Winnie the Pooh need to be declined. [52]

In 2023, in-country access was blocked to Hugging Face, a company that keeps libraries including training information sets commonly utilized for large language models. [8] A subsidiary of the People’s Daily, the official newspaper of the Central Committee of the Chinese Communist Party, offers regional business with training information that CCP leaders think about permissible. [8] In 2024, individuals’s Daily released a LLM-based tool called Easy Write. [53]

Microsoft has warned that the Chinese federal government uses generative artificial intelligence to interfere in foreign elections by spreading disinformation and provoking discussions on divisive political issues. [54] [55] [56]

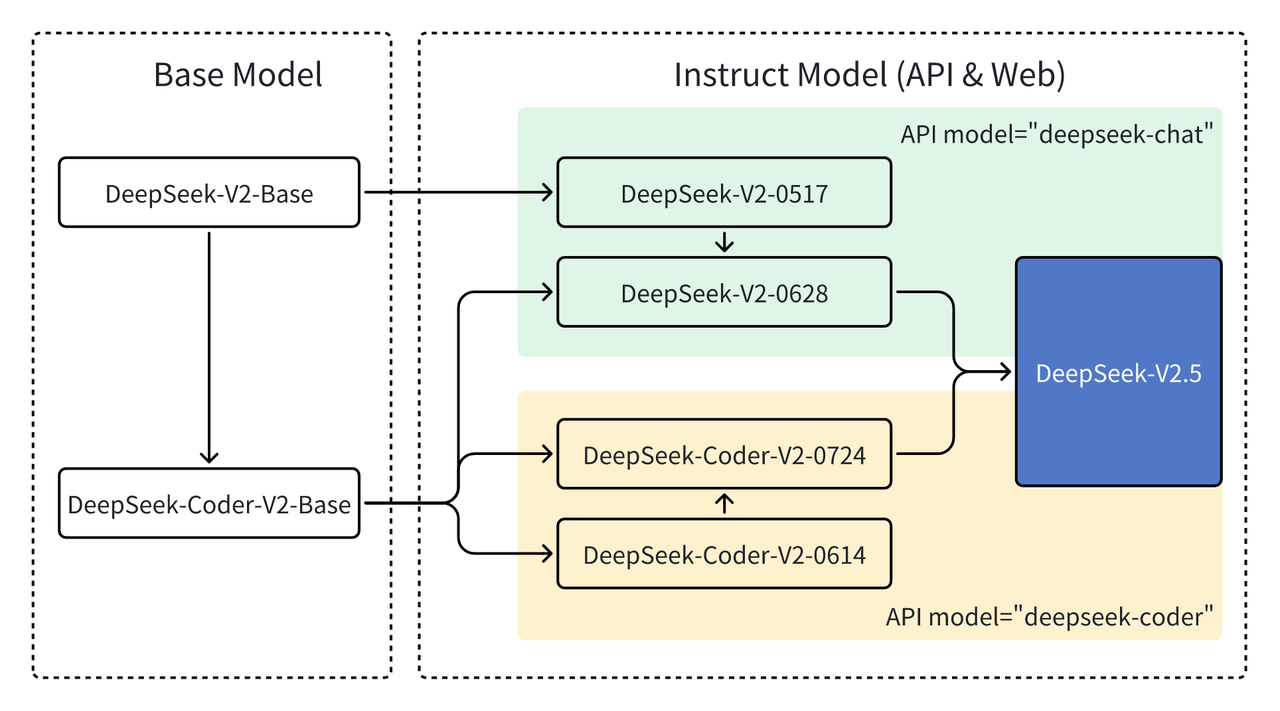

The Chinese expert system design DeepSeek has been reported to decline to answer questions relating to aspects of the 1989 Tiananmen Square demonstrations and massacre, persecution of Uyghurs, comparisons in between Xi Jinping and Winnie the Pooh or human rights in China. [57] [58] [59]

Impact

Economic impact

Most agencies [who?] hold positive views about AI’s economic effect on China’s long-term financial growth. In the past, standard markets in China have actually struggled with the boost in labor costs due to the growing aging population in China and the low birth rate. With the deployment of AI, operational expenses are anticipated to lower while an increase in efficiency produces revenue development. [60] Some highlight the value of a clear policy and governmental assistance in order to conquer adoption barriers including costs and lack of appropriately trained technical skills and AI awareness. [61] However, there are issues about China’s deepening income inequality and the ever-expanding imbalanced labor market in China. Low- and medium-income employees may be the most negatively affected by China’s AI advancement since of increasing demands for workers with innovative abilities. [61] Furthermore, China’s economic development might be disproportionately divided as a majority of AI-related industrial development is concentrated in coastal areas instead of inland. [61]

A prominent decision by the Beijing Internet Court has ruled that AI-generated material is entitled to copyright security. [28]:98

Military effect

China seeks to build a “world-class” armed force by “intelligentization” with a particular focus on making use of unmanned weapons and artificial intelligence. [62] [63] It is researching different types of air, land, sea, and undersea self-governing lorries. In the spring of 2017, a civilian Chinese university with ties to the military demonstrated an AI-enabled swarm of 1,000 unoccupied aerial cars at an airshow. A media report released afterwards showed a computer system simulation of a comparable swarm formation finding and destroying a rocket launcher. [4]:23 Open-source publications showed that China is also developing a suite of AI tools for cyber operations. [64] [4]:27 Chinese development of military AI is mainly affected by China’s observation of U.S. plans for defense innovation and worries of a widening “generational space” in comparison to the U.S. armed force. Similar to U.S. military ideas, China intends to utilize AI for exploiting big troves of intelligence, generating a common operating picture, and speeding up battlefield decision-making. [64] [4]:12 -14 The Chinese Multi-Domain Precision Warfare (MDPW) is considered China’s reaction to the U.S. Joint All-Domain Command and Control (JADC2) method, which seeks to incorporate sensors and weapons with AI and a vigorous network. [65] [66]

Twelve classifications of military applications of AI have been determined: UAVs, USVs, UUVs, UGVs, smart munitions, smart satellites, ISR (Intelligence, Surveillance and Reconnaissance) software, automated cyber defense software application, automated cyberattack software, choice assistance, software, automated rocket launch software application, and cognitive electronic warfare software application. [67]

China’s management of its AI ecosystem contrasts with that of the United States. [4]:6 In basic, couple of limits exist between Chinese industrial companies, university research study labs, the military, and the central federal government. As an outcome, the Chinese government has a direct ways of assisting AI advancement priorities and accessing technology that was ostensibly established for civilian purposes. To even more strengthen these ties the Chinese government produced a Military-Civil Fusion Development Commission which is meant to speed the transfer of AI technology from commercial business and research study organizations to the military in January 2017. [2] [4]:19 In addition, the Chinese federal government is leveraging both lower barriers to data collection and lower expenses of data labeling to develop the large databases on which AI systems train. [68] According to one estimate, China is on track to possess 20% of the world’s share of information by 2020, with the possible to have more than 30% by 2030. [64] [4]:12

China’s centrally directed effort is investing in the U.S. AI market, in business working on militarily pertinent AI applications, possibly approving it legal access to U.S. innovation and copyright. [69] Chinese endeavor capital financial investment in U.S. AI companies between 2010 and 2017 totaled an estimated $1.3 billion. [70] [64] In September 2022, the U.S. Biden administration released an executive order to prevent foreign financial investments, “particularly those from rival or adversarial nations,” from investing in U.S. technology firms, due to U.S. national security issues. [71] [72] The order covers fields of U.S. technologies in which Chinese government has been investing, including “microelectronics, synthetic intelligence, biotechnology and biomanufacturing, quantum computing, [and] innovative tidy energy.” [71] [72]

In 2024, scientists from individuals’s Liberation Army Academy of Military Sciences were reported to have established a military tool utilizing Llama, which Meta Platforms stated was unapproved due to its model use restriction for military functions. [73] [74]

Academia

Although in 2004, Peking University presented the first academic course on AI which led other Chinese universities to adopt AI as a discipline, specifically considering that China deals with challenges in recruiting and maintaining AI engineers and scientists. [21] Over half of the information scientists in the United States have actually been working in the field for over 10 years, while roughly the same percentage of information researchers in China have less than 5 years of experience. As of 2017, less than 30 Chinese Universities produce AI-focused professionals and research study items. [61]:8 Although China went beyond the United States in the number of research study papers produced from 2011 to 2015, the quality of its published documents, as judged by peer citations, ranked 34th globally. [75] China specifically wish to address military applications and so the Beijing Institute of Technology, one of China’s premier institutes for weapons research, just recently established the very first children’s curriculum in military AI in the world. [76]

In 2019, 34% of Chinese students studying in the AI field remained in China for work. [77] According to a database preserved by an American thinktank, the percentage increased to 58% in 2022. [77]

Ethical issues

For the previous years, there are conversations about AI safety and ethical concerns in both personal and public sectors. In 2021, China’s Ministry of Science and Technology published the very first national ethical guideline, ‘the New Generation of Artificial Intelligence Ethics Code’ on the subject of AI with particular focus on user defense, information privacy, and security. [78] This document acknowledges the power of AI and fast innovation adaptation by the huge corporations for user engagements. The South China Morning Post reported that humans shall stay in full decision-making power and rights to opt-in/-out. [78] Before this, the Beijing Academy of Artificial Intelligence released the Beijing AI principles requiring necessary requirements in long-term research study and preparation of AI ethical principles. [79]

Data security has actually been the most typical topic in AI ethical discussion worldwide, and lots of nationwide governments have developed legislation addressing information personal privacy and security. The Cybersecurity Law of the People’s Republic of China was enacted in 2017 aiming to address brand-new obstacles raised by AI development. [80] [initial research?] In 2021, China’s new Data Security Law (DSL) was gone by the PRC congress, establishing a regulatory structure categorizing all type of data collection and storage in China. [81] This suggests all tech business in China are required to classify their information into categories listed in Digital Subscriber Line (DSL) and follow particular standards on how to govern and manage data transfers to other parties. [81]

Judicial system

In 2019, the city of Hangzhou developed a pilot program synthetic intelligence-based Internet Court to adjudicate disagreements associated with ecommerce and internet-related intellectual residential or commercial property claims. [82]:124 Parties appear before the court via videoconference and AI evaluates the proof presented and applies relevant legal standards. [82]:124

Because some controversial cases that drew public criticism for their low punishments have been withdrawn from China Judgments Online, there are concerns about whether AI based upon fragmented judicial data can reach impartial decisions. [83] Zhang Linghan, professor of law at the China University of Government and Law, writes that AI-technology business might erode judicial power. [84] Some scholars argued that “increasing party management, political oversight, and minimizing the discretionary area of judges are intentional goals of SCR [clever court reform]” [85]

Leading companies

Leading AI-centric companies and start-ups consist of Baidu, Tencent, Alibaba, SenseTime, 4Paradigm and Yitu Technology. [86] Chinese AI companies iFlytek, SenseTime, Cloudwalk and DJI have actually gotten attention for facial acknowledgment, sound acknowledgment and drone innovations. [87]

China’s government takes a market-oriented approach to AI, and has sought to motivate private tech companies in establishing AI. [25]:281 In 2018, it designated Baidu, Alibaba, iFlytek, Tencent, and SenseTime as “AI champions”. [25]:281

In 2023, Tencent debuted its big language design Hunyuan for business usage on Tencent Cloud. [88]

New leading AI start-ups include Baichuan, Zhipu AI, Moonshot AI and MiniMax which were applauded by financiers as China’s brand-new “AI Tigers” in 2024. [32] 01. AI has also been touted as a leading startup. [89]

Assessment

Academic Jinghan Zeng argued the Chinese federal government’s dedication to worldwide AI management and technological competition was driven by its previous underperformance in development which was seen by the CCP as a part of the century of humiliation. [90] According to Zeng, there are traditionally embedded reasons for China’s stress and anxiety towards protecting a global technological supremacy – China missed both industrial revolutions, the one beginning in Britain in the mid-18th century, and the one that stemmed in America in the late-19th century. [90] Therefore, China’s federal government desires to benefit from the technological revolution in today’s world led by digital innovation including AI to resume China’s “rightful” location and to pursue the national renewal proposed by Xi Jinping. [90]

A short article released by the Center for a Brand-new American Security concluded that “Chinese government officials demonstrated incredibly keen understanding of the problems surrounding AI and global security. This includes knowledge of the U.S. AI policy discussions,” and recommended that “the U.S. policymaking community to similarly focus on cultivating competence and understanding of AI developments in China” and “funding, focus, and a determination among U.S. policymakers to drive large-scale needed modification.” [35] A post in the MIT Technology Review similarly concluded: “China may have unparalleled resources and huge untapped capacity, however the West has world-leading competence and a strong research culture. Instead of worry about China’s progress, it would be wise for Western nations to focus on their existing strengths, investing heavily in research and education. ” [91]

The Chinese federal government’s censorship program has stunted the advancement of generative expert system [7] [8]

In a 2021 text, the Research Centre for a Holistic Approach to National Security at the China Institutes of Contemporary International Relations composed that the advancement of AI produces obstacles for holistic nationwide security, including the dangers that AI will heighten social stress or have destabilizing impacts on international relations. [28]:49

Writing from a Chinese Marxist view, academics consisting of Gao Qiqi and Pan Enrong compete that capitalist application of AI will result in higher oppression of workers and more major social problems. [28]:90 Gao points out how the development of AI has increased the power of platform business like Meta, Twitter, and Alphabet, causing greater capital accumulation and political power in less economic actors. [28]:90 According to Gao, the state needs to be the main accountable star in the area of generative AI (producing brand-new material like music or video). [28]:92 Gao composes that military usage of AI threats escalating military competitors in between countries which the impact of AI in military matters will not be limited to one nation but will have spillover results. [28]:91

Dialogues between Chinese and Western AI professionals about the existential threat from expert system have actually occurred. [92]

Public polling

The Chinese public is usually optimistic regarding AI. [25]:283 [28]:101 A 2021 study carried out throughout 28 countries found that 78% of the Chinese public thinks the advantages of AI exceed the threats, the greatest of any nation in the study. [25]:283 In 2024, a survey of elite Chinese college student discovered that 80% concurred or highly concurred that AI will do more good than harm for society, and 31% thought it must be controlled by the federal government. [93]

Human rights

The extensively used AI facial acknowledgment has raised issues. [94] According to The New York Times, deployment of AI facial recognition innovation in the Xinjiang area to find Uyghurs is “the first known example of a government intentionally utilizing expert system for racial profiling,” [95] which is said to be “among the most striking examples of digital authoritarianism.” [96] Researchers have actually discovered that in China, areas experiencing higher rates of unrest are connected with increased state acquisition of AI facial recognition technology, especially by local community authorities departments. [97] [98]

Expert system.

Expert system arms race

China Brain Project

Fifth generation computer system

List of synthetic intelligence companies

Regulation of expert system

References

^ a b Chang, Huey-Meei; Hannas, William C. (2022-06-22), “Foreign support, alliances, and technology transfer”, Chinese Power and Expert System (1 ed.), London: Routledge, pp. 36-54, doi:10.4324/ 9781003212980-4, ISBN 978-1-003-21298-0

^ a b c He, Yujia (2017 ). How China is getting ready for an AI-powered Future (PDF). Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2021-02-15. Retrieved 2020-04-30.

^ a b c d e Luong, Ngor; Fedasiuk, Ryan (2022-06-22), “State strategies, research, and financing”, Chinese Power and Artificial Intelligence (1 ed.), London: Routledge, pp. 3-18, doi:10.4324/ 9781003212980-2, ISBN 978-1-003-21298-0

^ a b c d e f g Kania, Elsa B. (November 28, 2017). Battlefield Singularity: Artificial Intelligence, Military Revolution, and China’s Future Military Power. Washington D.C: Center for a Brand-new American Security. OCLC 1029611044. Archived from the initial on January 14, 2024. Retrieved February 16, 2024.

^ Allen, Gregory (11 October 2022). “Choking off China’s Access to the Future of AI”. Center for Strategic and International Studies. Archived from the original on 12 October 2022. Retrieved 12 October 2022.

^ Allen, Gregory C.; Benson, Emily (2023-03-01). “Clues to the U.S.-Dutch-Japanese Semiconductor Export Controls Deal Are Hiding in Plain Sight”. Center for Strategic and International Studies. Archived from the original on 2023-03-03. Retrieved 2023-03-03.

^ a b Zhang, Daqiu; Lin, Yujie (2024-07-02). “生成中国式AI : 审查之外 , 科技公司的烦恼清单” [Building a Chinese AI: Beyond censorship, tech companies’ list of worries] Initium Media (in Simplified Chinese). Archived from the original on 2024-07-11. Retrieved 2024-07-11.

^ a b c d e Lin, Liza (July 15, 2024). “China Puts Power of State Behind AI-and Risks Strangling It”. The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the initial on July 16, 2024. Retrieved July 16, 2024.

^ a b c d 蔡自兴 (13 August 2016). “中国人工智能40 年”. 科技导报 (in Chinese). 34 (15 ): 12-32. doi:10.3981/ j.issn.1000-7857.2016.15.001 (non-active 1 November 2024). ISSN 1000-7857. Archived from the original on 2022-01-20. Retrieved 2022-02-07. mention journal: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of November 2024 (link).

^ “Introduction to the Chinese Association of Expert System”. 中国人工智能学会.

^ Liu, Wei (2023 ), Liu, Wei (ed.), “From Adjustment to Innovation: How China’s Economic Structure Has Been Upgraded”, China’s 40 Years of Reform, Understanding China, Singapore: Springer Nature Singapore, pp. 11-33, doi:10.1007/ 978-981-19-8505-8_2, ISBN 978-981-19-8504-1.

^ a b “人民网 世界人工智能国际联合大会今秋将首次在中国举行– 中国科学院”. www.cas.cn. Archived from the original on 2023-05-04. Retrieved 2023-05-05.

^ “科学网-首届吴文俊人工智能科学技术奖颁奖”. news.sciencenet.cn. Archived from the original on 2023-05-04. Retrieved 2023-05-05.

^ a b c d e “State Council Notice on the Issuance of the Next Generation Expert System Development Plan” (PDF). New America. Archived (PDF) from the original on April 13, 2018. Retrieved April 2, 2018.

^ Laskai, Lorand (29 January 2018). “Civil-Military Fusion: The Missing Link Between China’s Technological and Military Rise”. Council on Foreign Relations. Archived from the original on 18 July 2020. Retrieved 3 June 2020.

^ “中国科学报” 人工智能+” 应上升为国家战略– 中国科学院”. www.cas.cn. Archived from the original on 2023-05-04. Retrieved 2023-05-05.

^ “人民网 强强联合建医疗” 阿尔法狗” 人工智能将问诊肿瘤– 中国科学院”. www.cas.cn. Archived from the initial on 2023-05-04. Retrieved 2023-05-05.

^ a b Milmo, Dan; Hawkins, Amy (2024-05-18). “How China is utilizing AI news anchors to provide its propaganda”. The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Archived from the initial on 2024-05-25. Retrieved 2024-05-19.

^ Kuo, Lily (2018-11-09). “World’s very first AI news anchor unveiled in China”. The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Archived from the original on 2024-02-20. Retrieved 2024-05-19.

^ Steger, Isabella (2019-02-20). “Chinese state media’s latest innovation is an AI female news anchor”. Quartz. Archived from the original on 2024-05-19. Retrieved 2024-05-19.

^ a b Cyranoski, David (January 17, 2018). “China gets in the fight for AI skill”. Nature. 553 (7688 ): 260-261. Bibcode:2018 Natur.553..260 C. doi:10.1038/ d41586-018-00604-6. PMID 29345655.

^ Liu, Zhiyi; Zheng, Yejie (2022-04-03). “Development paradigm of artificial intelligence in China from the point of view of digital economics”. Journal of Chinese Economic and Business Studies. 20 (2 ): 207-217. doi:10.1080/ 14765284.2022.2081485. ISSN 1476-5284. S2CID 249301337.

^ “自动化所研发出跨模态通用人工智能平台” 紫东太初”– 中国科学院”. www.cas.cn. Archived from the initial on 2023-05-04. Retrieved 2023-05-05.

^ “Beijing-funded AI language design tops Google and OpenAI in raw numbers”. South China Morning Post. 2021-06-02. Archived from the initial on 2023-11-19. Retrieved 2024-05-21.

^ a b c d e f g h Zhang, Angela Huyue (2024 ). High Wire: How China Regulates Big Tech and Governs Its Economy. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ oso/9780197682258.001.0001. ISBN 9780197682258.

^ Zhang, Laney (April 26, 2023). “China: Provisions on Deep Synthesis Technology Enter into Effect”. Law Library of Congress. Archived from the initial on 2024-08-16. Retrieved 2024-08-19.

^ “Huawei unveils Arabic LLM, new information centre in Egypt as part of generative AI push”. South China Morning Post. 2024-05-21. Archived from the original on 2024-05-25. Retrieved 2024-05-21.

^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Bachulska, Alicja; Leonard, Mark; Oertel, Janka (2 July 2024). The Idea of China: Chinese Thinkers on Power, Progress, and People (EPUB). Berlin, Germany: European Council on Foreign Relations. ISBN 978-1-916682-42-9. Archived from the initial on 17 July 2024. Retrieved 22 July 2024.

^ Bandurski, David (2024-12-20). “AI for All”. China Media Project. Archived from the initial on 2024-12-20. Retrieved 2024-12-22.

^ Zhuang, Sylvie (21 May 2024). “China rolls out large language model AI based upon Xi Jinping Thought”. South China Morning Post. Archived from the original on 21 May 2024. Retrieved 21 May 2024.

^ “Baidu, SenseTime lead China’s market for business-focused LLMs, says IDC”. South China Morning Post. 2024-08-22. Archived from the initial on 2024-08-27. Retrieved 2024-08-24.

^ a b “China’s 4 brand-new ‘AI tigers’ emerge as financier favourites”. South China Morning Post. 2024-04-19. Retrieved 2024-08-24.

^ “China’s AI start-ups race for clients as titans like Alibaba cut prices”. Nikkei Asia. Retrieved 2024-08-24.

^ “Chinese AI companies combat to stand out from competitors in text-to-video market”. South China Morning Post. 2024-08-08. Retrieved 2024-08-24.

^ a b Allen, Gregory C. (2019 ). Understanding China’s AI Strategy: Clues to Chinese Strategic Thinking on Expert System and National Security (Report). Center for a Brand-new American Security. JSTOR resrep20446. Archived from the initial on 2019-02-07. Retrieved 2019-03-11.

^ Sutter, Karen M. ; Arnold, Zachary (2022-06-22), “China’s AI companies: Hybrid gamers”, Chinese Power and Expert System (1 ed.), London: Routledge, pp. 19-35, doi:10.4324/ 9781003212980-3, ISBN 978-1-003-21298-0

^ Lan, Xiaohuan (2024 ). How China Works: An Introduction to China’s State-led Economic Development. Translated by Topp, Gary. Palgrave Macmillan. doi:10.1007/ 978-981-97-0080-6. ISBN 978-981-97-0079-0.

^ a b Ashwin Acharya; Zachary Arnold (December 2019). “Chinese Public AI R&D Spending: Provisional Findings”. Center for Security and Emerging Technology. doi:10.51593/ 20190031. S2CID 242961679. Archived from the initial on 2024-04-10. Retrieved 2024-04-10.

^ Larson, Christina (8 February 2018). China’s massive investment in synthetic intelligence has a perilous disadvantage (Report). Science. doi:10.1126/ science.aat2458.

^ a b 21世纪经济报道 (2021-07-10). “解码人工智能” 国家队””. finance.sina.com.cn. Archived from the original on 2023-04-09. Retrieved 2024-02-16. mention web: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link).

^ Tilley, Aaron. “China’s Rise In The Global AI Race Becomes It Takes Control Of The Final ImageNet Competition”. Forbes. Archived from the original on 2019-05-28. Retrieved 2020-04-30.

^ “Beijing to Judge Every Resident Based on Behavior by End of 2020”. Bloomberg News. Archived from the initial on 2020-05-16.

^ a b Zhang, Daniel; Mishra, Saurabh; Brynjolfsson, Erik; Etchemendy, John; Ganguli, Deep; Grosz, Barbara; Lyons, Terah; Manyika, James; Niebles, Juan Carlos (2021-03-08), The AI Index 2021 Annual Report, arXiv:2103.06312.

^ Heikkilä, Melissa (June 9, 2021). “Meet Wu Dao 2.0, the Chinese AI design making the West sweat”. Politico. Archived from the initial on April 7, 2023. Retrieved April 7, 2023.

^ Ho, C. (October 15, 2024). “PRC Launches First Algorithm Registration Center, Strengthening AI and Data Regulation”. Jamestown Foundation. Retrieved 2024-10-18.

^ Li, David Daokui (2024 ). China’s World View: Demystifying China to Prevent Global Conflict. New York City, NY: W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 978-0393292398.

^ Li, Daitian; Tong, Tony W.; Xiao, Yangao (2021-02-18). “Is China Emerging as the Global Leader in AI?”. Harvard Business Review. ISSN 0017-8012. Archived from the initial on 2024-01-20. Retrieved 2024-02-16.

^ Knight, Will (January 24, 2023). “China Is the World’s Biggest Face Recognition Dealer”. Wired. ISSN 1059-1028. Archived from the original on 2024-02-25. Retrieved 2024-02-25.

^ Bandurski, David (April 14, 2023). “Bringing AI to the Party”. China Media Project. Archived from the original on April 15, 2023. Retrieved April 15, 2023.

^ Liu, Qianer (2023-07-11). “China to lay down AI guidelines with focus on content control”. Financial Times. Archived from the initial on 2024-05-25. Retrieved 2024-05-21.

^ “China is fortifying the great firewall software for the AI age”. The Economist. December 26, 2023. ISSN 0013-0613. Archived from the initial on 2023-12-26. Retrieved 2023-12-26.

^ a b McMorrow, Ryan; Hu, Tina (July 17, 2024). “China deploys censors to develop socialist AI”. Financial Times. Archived from the original on July 17, 2024. Retrieved July 17, 2024.

^ Colville, Alex (2024-11-27). “The Party in the Machine”. China Media Project. Archived from the original on 2024-12-02. Retrieved 2024-11-30.

^ Lyngaas, Sean (2023-09-07). “Suspected Chinese operatives utilizing AI generated images to spread disinformation among US voters, Microsoft says”. CNN. Archived from the original on 2024-04-02. Retrieved 2024-04-08.

^ Milmo, Dan (2024-04-05). “China will use AI to interfere with elections in the US, South Korea and India, Microsoft alerts”. The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Archived from the original on 2024-05-25. Retrieved 2024-04-08.

^ Farrell, James (April 5, 2024). “China Eying Election Disruption Campaigns-Including With AI, Microsoft Says”. Forbes. Archived from the original on April 8, 2024. Retrieved April 8, 2024.

^ Field, Matthew; Titcomb, James (27 January 2025). “Chinese AI has actually sparked a $1 trillion panic – and it does not appreciate free speech”. The Daily Telegraph. ISSN 0307-1235. Retrieved 27 January 2025.

^ Steinschaden, Jakob (27 January 2025). “DeepSeek: This is what live censorship appears like in the Chinese AI chatbot”. Trending Topics. Retrieved 27 January 2025.

^ Lu, Donna (28 January 2025). “We tried DeepSeek. It worked well, until we asked it about Tiananmen Square and Taiwan”. The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 30 January 2025.

^ “How China Is Using AI to Fuel the Next Industrial Revolution”. Time. Archived from the initial on 2022-02-05. Retrieved 2022-02-04.

^ a b c d “Expert system: Implications for China”. McKinsey & Company. Archived from the initial on 2024-02-04. Retrieved 2024-02-16.

^ Bresnick, Sam (June 2024). “China’s Military AI Roadblocks”. Center for Security and Emerging Technology. doi:10.51593/ 20230042 (inactive 1 November 2024). Archived from the initial on 2024-06-18. Retrieved 2024-06-18. mention web: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of November 2024 (link).

^ Takagi, Koichiro (November 16, 2022). “Xi Jinping’s Vision for Artificial Intelligence in the PLA”. The Diplomat. Archived from the initial on February 18, 2024. Retrieved February 17, 2024.

^ a b c d Artificial Intelligence and National Security (PDF). Washington, DC: Congressional Research Service. 2019. Archived (PDF) from the initial on 2020-05-08. Retrieved 2020-04-30. This short article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

^ Magnuson, Stew (July 13, 2023). “China Pursues Its Own Version of JADC2”. National Defense. Archived from the original on February 18, 2024. Retrieved February 17, 2024.

^ “China Military Power Report Examines Changes in Beijing’s Strategy”. U.S. Department of Defense. November 29, 2022. Archived from the initial on May 25, 2024. Retrieved February 17, 2024.

^ Fedasiuk, Ryan (August 2020). Chinese Perspectives on AI and Future Military Capabilities (Report). Center for Security and Emerging Technology. doi:10.51593/ 20200022.

^ Knight, Will (October 10, 2017). “China’s AI Awakening中国 人工智能 的崛起”. MIT Technology Review. Archived from the original on 2020-05-13. Retrieved 2020-04-30.

^ Mozur, Paul; Markoff, John (2017-05-27). “Is China Outsmarting America in A.I.?”. The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the initial on 2020-04-07. Retrieved 2020-04-30.

^ Brown, Michael; Singh, Pavneet (2018 ). China’s Technology Transfer Strategy: How Chinese Investments in Emerging Technology Enable A Strategic Competitor to Access the Crown Jewels of U.S. Innovation (PDF). Defense Innovation Unit Experimental. p. 29. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2020-04-12. Retrieved 2020-04-30.

^ a b Kan, Michael (September 15, 2022). “Biden Curbs China’s Investment in US Tech Firms With New Executive Order”. PC Magazine. Archived from the original on February 20, 2024. Retrieved February 19, 2024.

^ a b Sanger, David E. (2022-09-15). “Biden Issues New Order to Block Chinese Investment in Technology in the U.S.” The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 2024-02-20. Retrieved 2024-02-20.

^ Cheung, Sunny (October 31, 2024). “PRC Adapts Meta’s Llama for Military and Security AI Applications”. Jamestown Foundation. Archived from the original on 2024-11-02. Retrieved 2024-11-03.

^ Pomfret, James; Pang, Jessie (November 1, 2024). “Chinese researchers establish AI design for military usage on back of Meta’s Llama”. Reuters. Retrieved November 1, 2024.

^ “Which nations and universities are leading on AI research?”. Times Higher Education. 2017-05-22. Archived from the original on 2020-03-02. Retrieved 2020-04-30.

^ “China’s brightest children hired to establish AI ‘killer bots'”. South China Morning Post. 2018-11-08. Archived from the initial on 2020-01-09. Retrieved 2020-04-30.

^ a b “China has become a scientific superpower”. The Economist. ISSN 0013-0613. Archived from the initial on 2024-09-26. Retrieved 2024-09-27.

^ a b “Chinese AI has new ethical guidelines that curb Big Tech’s algorithms”. South China Morning Post. 2021-10-03. Archived from the initial on 2022-02-03. Retrieved 2022-02-04.

^ Wu, Wenjun; Huang, Tiejun; Gong, Ke (March 2020). “Ethical Principles and Governance Technology Development of AI in China”. Engineering. 6 (3 ): 302-309. Bibcode:2020 Engin … 6..302 W. doi:10.1016/ j.eng.2019.12.015.

^ “Translation: Cybersecurity Law of the People’s Republic of China (Effective June 1, 2017)”. DigiChina. Archived from the original on 2022-02-04. Retrieved 2022-02-04.

^ a b Horwitz, Josh (2021-08-27). “China’s coming information laws leave companies with more concerns than answers”. Reuters. Archived from the initial on 2022-02-04. Retrieved 2022-02-04.

^ a b Šimalčík, Matej (2023 ). “Rule by Law”. In Kironska, Kristina; Turscanyi, Richard Q. (eds.). Contemporary China: a New Superpower?. Routledge. pp. 114-127. doi:10.4324/ 9781003350064-12. ISBN 978-1-03-239508-1.

^ Zhabina, Alena (January 20, 2023). “How China’s AI is automating the legal system”. Deutsche Welle. Archived from the original on March 29, 2024. Retrieved May 25, 2024.

^ Chen, Stephen (2022-07-13). “China’s court AI reaches into every corner of justice system: report”. South China Morning Post. Archived from the initial on 2024-03-31. Retrieved 2024-05-25. [H] umans will slowly lose totally free will with an increasing reliance on technology”, she stated in a paper published in the domestic peer-reviewed journal Law and Social Development on Sunday. The wise court system, constructed with the deep participation of China’s tech giants, would also pass too much power into the hands of a few technical experts who composed the code, developed algorithms or supervised the database. “We need to look out to the erosion of judicial power by innovation companies and capital,” she added.

^ Papagianneas, Straton; Junius, Nino (November 2023). “Fairness and justice through automation in China’s clever courts”. Computer Law & Security Review. 51: 100-101. doi:10.1016/ j.clsr.2023.105897. hdl:10067/ 2001290151162165141. Archived from the original on 2024-05-26. Retrieved 2024-05-26 – by means of Elsevier Science Direct.

^ Pham, Sherisse (2018 ). “Chinese AI start-up dwarfs international competitors with $4.5 billion evaluation”. CNN. Archived from the initial on 9 April 2018. Retrieved 10 April 2018.

^ “China ramps up tech education to end up being expert system leader”. NBC News. 4 January 2020. Archived from the original on 2020-01-10. Retrieved 2020-01-10.

^ Cao, Ann (2023-09-07). “Tencent launches Hunyuan structure AI design for business”. South China Morning Post. Archived from the initial on 2024-06-03. Retrieved 2024-06-03.

^ Olcott, Eleanor (3 May 2024). “4 start-ups lead China’s race to match OpenAI’s ChatGPT”. Financial Times. Archived from the original on 8 September 2024. Retrieved 27 October 2024.

^ a b c Zeng, Jinghan (2021-09-16). “Securitization of Expert System in China”. The Chinese Journal of International Politics. 14 (3 ): 417-445. doi:10.1093/ cjip/poab005. ISSN 1750-8916.

^ Knight, Will (October 10, 2017). “China’s AI Awakening”. MIT Technology Review. Archived from the initial on March 24, 2018. Retrieved April 3, 2018.

^ Guest, Peter (November 29, 2024). “Inside the AI back-channel in between China and the West”. The Economist. ISSN 0013-0613. Retrieved 2024-12-08.

^ Corvino, Nick; Li, Boshen (August 23, 2024). “Survey: How Do Elite Chinese Students Feel About the Risks of AI?”. Jamestown Foundation. Archived from the initial on 2024-08-24. Retrieved 2024-08-23.

^ Beraja, Martin; Kao, Andrew; Yang, David Y; Yuchtman, Noam (2023-06-23). “AI-tocracy”. The Quarterly Journal of Economics. 138 (3 ): 1349-1402. doi:10.1093/ qje/qjad012. ISSN 0033-5533.

^ Mozur, Paul (2019-04-14). “One Month, 500,000 Face Scans: How China Is Using A.I. to Profile a Minority”. The New York City Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 2019-06-08. Retrieved 2024-02-25.

^ Sahin, Kaan (December 18, 2020). “The West, China, and AI security”. Atlantic Council. Archived from the initial on February 26, 2024. Retrieved February 25, 2024.

^ “Autocracy and AI Innovation”. Stanford University Center on China’s Economy and Institutions. Stanford University. July 1, 2022. Archived from the initial on February 26, 2024. Retrieved February 25, 2024.

^ “China’s AI-Tocracy Quells Protests and Boosts AI Innovation”. IEEE Spectrum. Archived from the original on 2024-02-26. Retrieved 2024-02-26.

Further reading

Hannas, William C.; Chang, Huey-Meei, eds. (29 July 2022). Chinese Power and Expert System: Perspectives and Challenges (1st ed.). London: Routledge.